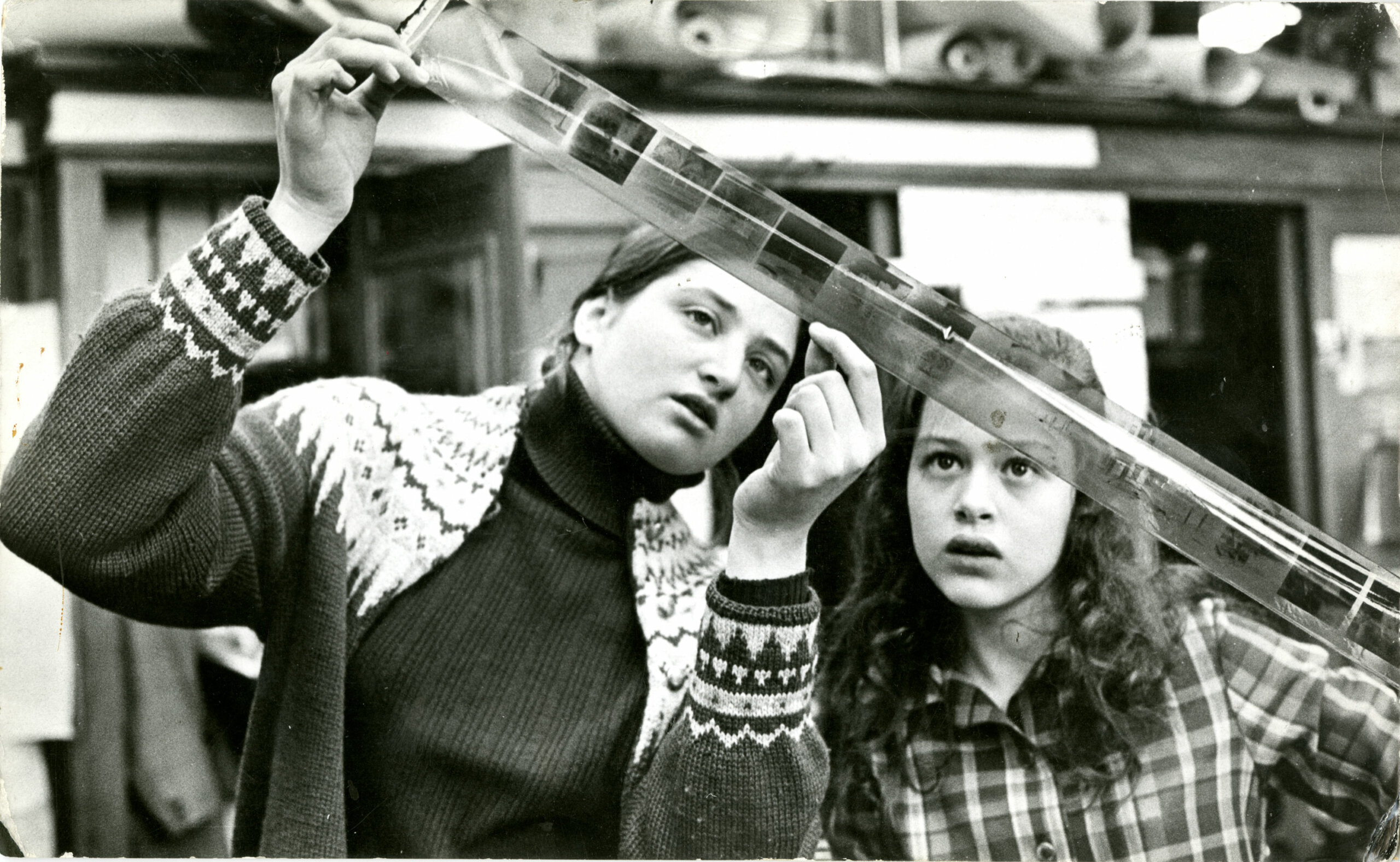

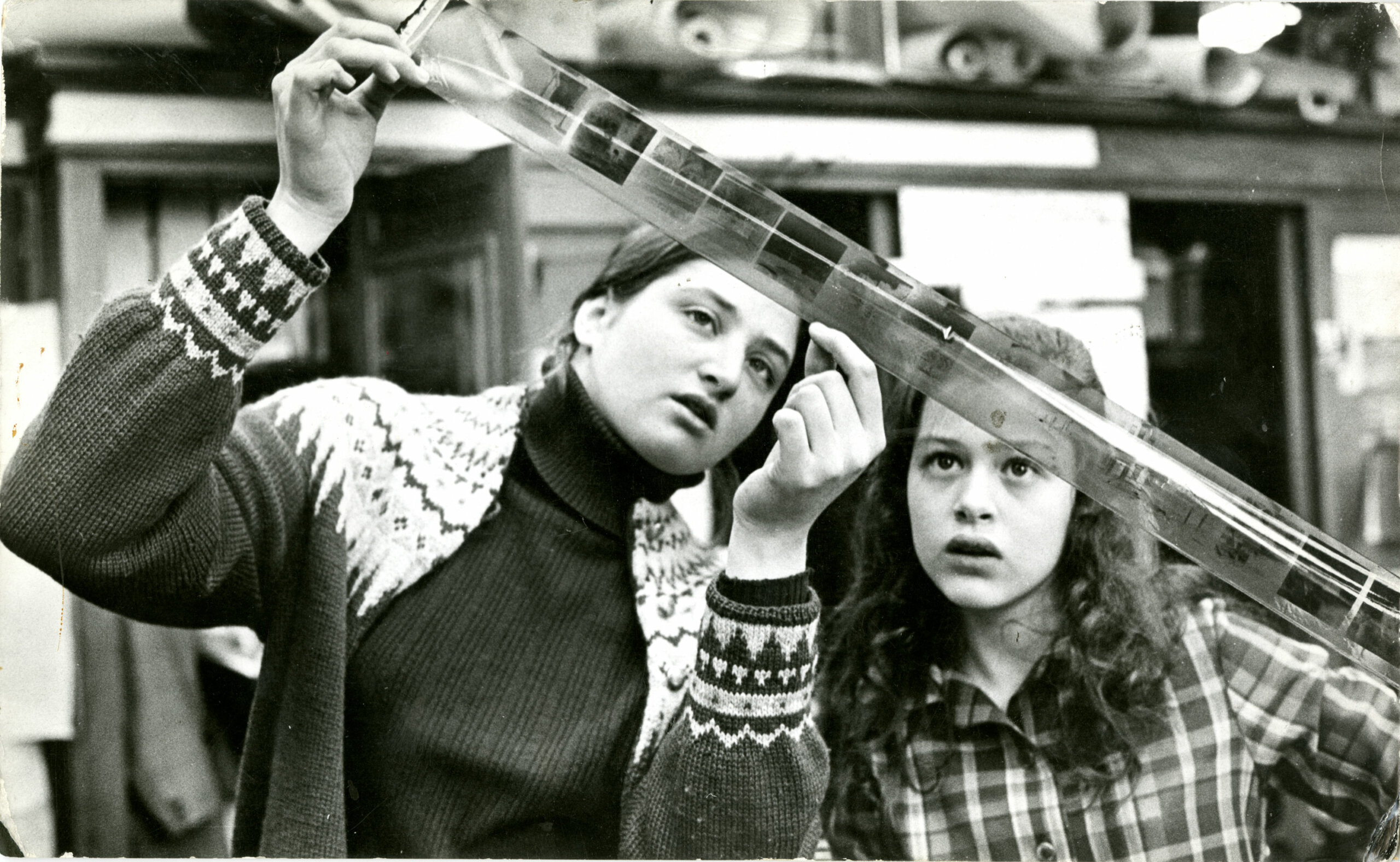

Susan Meiselas teaching elementary school student, South Bronx, New York, 1972. Photograph by Community Resources Institute. Courtesy Susan Meiselas Studio.

Susan Meiselas teaching elementary school student, South Bronx, New York, 1972. Photograph by Community Resources Institute. Courtesy Susan Meiselas Studio.

The 2024 WOPHA Congress, titled How Photography Teaches Us to Live Now, is a creative convening and exhibition series scheduled from October 23-26, 2024, across various locations in South Florida, including the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM).

Organized by the Women Photographers International Archive (WOPHA) in collaboration with PAMM, the event seeks to spotlight the significant contributions of women and non-binary photographers in contemporary art and innovate approaches to photography education. Through interactive experiences such as photo walks, portfolio reviews, exhibitions, workshops, and panel discussions, the Congress intends to redefine traditional photography education.

The theme How Photography Teaches Us to Live Now will delve into various topics, including collaboration in photography, Caribbean photography history, and current debates in the field. It aims not only to advance WOPHA’s global mission but also to highlight South Florida as an emerging center for contemporary photography, fueled by its vibrant cultural landscape and diverse population.

Among the scheduled events are masterclasses and panel discussions led by renowned art historians, educators, and photographers, alongside a city-wide program of exhibitions across South Florida. Virtual modules will also be available, enhancing accessibility to a global audience.

Key speakers include Latinx art historian and curator Aldeide Delgado, Founder and Director of WOPHA; Andrea Jösch Krotki, Director of the Art School at Universidad Diego Portales (Chile); Susan Meiselas, Documentary photographer and President of the Magnum Foundation (USA); Muriel Hasbun, Artist and educator (El Salvador/USA); Rosell Meseguer (Spain), focusing on themes of memory and history; María Martínez Cañas (Cuba/USA), known for her experimental photography; José Antonio Navarrete (Venezuela/USA), specializing in Latin American art and photography; and Tatiana Flores (Venezuela/USA), whose research centers on Latin American and Caribbean art.

The four-day creative gathering, conceptualized by Aldeide Delgado, underscores the critical need for academic programs addressing the history of women in photography, despite the predominance of female students in the field globally. Delgado emphasizes the Congress’s role in initiating discussions on women, photography, and pedagogy as a foundational step toward establishing an educational hub dedicated to the study of photographic practices, criticism, and historiography.

This is why this year’s Congress marks the launch of the WOPHA Institute, a pioneering initiative that intends to challenge patriarchal norms and amplify the voices of women and non-binary photographers, while also responding to challenges in photography education, including declining enrollments and growing interest in alternative teaching methods, thereby advancing the field significantly.

The 2024 WOPHA Congress is set to be a pivotal event, fostering cultural partnerships and pushing the boundaries of photography education with a strong focus on inclusivity and innovation. To gain deeper insights into what’s ahead, we caught up with Aldeide Delgado, who shared her perspectives on the Congress’s mission, ambitious goals, key challenges, thematic focus, and the exciting new educational initiative launched by WOPHA.

In 2018, you co-founded the Women Photographers International Archive (WOPHA) alongside your partner in life, visual artist Francisco Maso, who has served as its creative director since inception. Considering WOPHA as the foundation of this Congress, could you briefly discuss how the organization has evolved since its establishment and highlight some of its most significant achievements to date?

Reflecting on the past six years, the process has been intense. Our evolution has focused on ensuring long-term sustainability, growing our operational budget, securing local, state, and federal government grants, and solidifying private and foundation contributions.

Additionally, we have built a portfolio of high-quality, mission-driven annual programs, including conferences, workshops, exhibitions, artist residencies, and publications. All while fomenting a global network of women’s photography organizations.

These administrative elements, while seemingly secondary, have been crucial in achieving our vision: to be a permanent archive that preserves, documents, and promotes the work of women and non-binary photographers for generations to come.

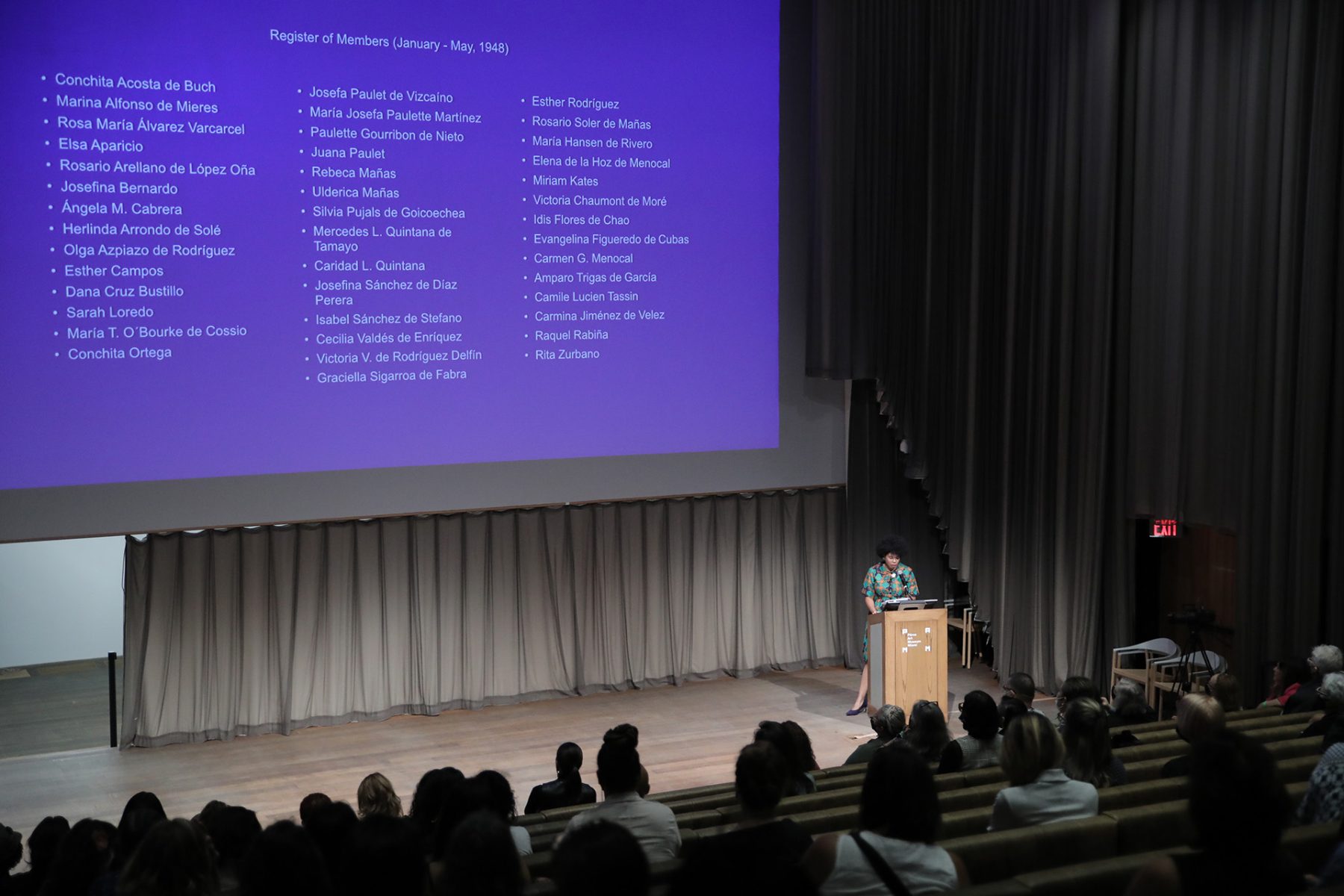

Our most significant achievement to date has been organizing the world’s first WOPHA Congress (November 17–20, 2021). This event brought together 44 art historians, curators, and artists, along with 40 women photography collectives and organizations, and more than 100 women photographers from around the world. The Congress presented seminal and emerging research, addressing both national and international discussions regarding women and feminism in the history of photography.

What are some of the biggest challenges you face in promoting and supporting women photographers, and how do you overcome them?

Building a new organization such as WOPHA has allowed me to problematize the Archive as a modern/colonial institution per se and question its systems of operation, categorization, and knowledge production. I have focused on critically thinking about the conceptual and geopolitical place of the organization, framed within border, feminist, decolonial, and archipelagic narratives while expanding its local, national, and international reach.

A significant challenge has been the experimentation that comes with rehearsing new models following a trial-and-error strategy. People working in traditional institutions often feel uncomfortable moving beyond established modes of thinking and working. However, gaining trust from key allies has been instrumental in our success.

There is also a lack of regionally diverse references and examples of other successful institutions that have excelled with a feminist methodology and governance. This gap has required us to build those references ourselves and develop our own methods while educating our team on what it means to work from a feminist perspective.

WOPHA functions as an organic entity with various individuals volunteering, collaborating, and supporting at different times.

Another major challenge we face is the vulnerability provoked by the lack of diverse sources of funding. The scarcity of resources leads to an overload of work for our team, who perform multiple tasks that would typically have independent positions in larger institutions. Overcoming these challenges has involved persistent effort and collaboration to create sustainable and impactful support, internally as an organization, but also for our community.

Why was this year’s Congress titled How Photography Teaches Us to Live Now, and what does this theme signify in the context of contemporary photography and artistic discourse?

The title of this year’s Congress, How Photography Teaches Us to Live Now, references visual artist and scholar Carmen Winant’s 2021 book, Instructional Photography: Learning How to Live Now. Winant’s work delves into how photographs can serve as more than just documentary evidence—they can act –and she demonstrates it through a curated selection of archival images– as guides, manuals, and educational tools. She coined the term “instructional photographs” to describe a kind of images, distinguished from traditional documentary photography, that actively teach us how to navigate life, how to see, or how to learn a new skill.

As I engaged with Winant’s book, I became increasingly interested in how pedagogies and curatorial practices can be integrated to foster more active audience participation in the conceptualization and experience of exhibitions. This is less about educational programming, and more about educational tools as art curating.

The notion of instruction is pivotal here—it’s a tool that can shift the audience from passive spectators to active participants without falling into the trap of didacticism or authoritarianism. I think this approach is particularly relevant for photography exhibitions and has been a topic of several discussions between visual artist and WOPHA Creative Director, Francisco Maso and myself. His own artwork in the past years has directly addressed the structure of manuals and instructions to radicalize the exhibition display and engage the audience meaningfully.

One of my primary goals for the 2024 WOPHA Congress as a photography-based, multi-modal, curatorial project was to expand the reach of the program beyond the traditional confines of the art museum and to impact a diverse range of audiences who interact with photography in their everyday lives. In the emerging art history of Miami, this is a significant act.

Additionally, this focus on teaching led me to reflect on the lack of scholarly studies focused on radical and experimental practices of photography education, especially in contrast to the growing body of research work on feminist curatorial and archival practices. While there has been significant theorization around these latter areas, teaching has not received the same level of scrutiny. This gap in the discourse became a central focus for this Congress, as we assume the incomplete task to reflect on women, photography, and pedagogies.

How did you select the featured speakers for this year’s Congress, and what criteria were essential in shaping the lineup? Can you highlight a few key themes or perspectives that each invited participant brings to the Congress?

I began the speakers’ selection for this year’s Congress with a clear starting point and set of critical questions: Even though 75% of photography students worldwide are women, there remains a glaring absence of academic programs specifically addressing the history of women in photography.

This led me to question the current state of photography education and the specific needs within this field. Who are the women who have played crucial roles as photography teachers, mentors, and educators? What have been their working conditions and contributions to the curriculum? What feminist pedagogies can be applied to the teaching of photography, and how do these impact the learning experience?

I sought out authors, scholars, and practitioners who have written, lectured, or published on these issues within culturally and geographically diverse contexts. However, I found very little information with a historiographical and critical approach to these topics. Faced with this challenge, I decided to shift my methodological approach.

Considering a history still waiting to be written, I proposed inviting those authors and educators who could contribute to shaping a new, decolonial and non-patriarchal photography curriculum, one that could eventually be part of the WOPHA Institute curriculum.

Given the breadth of this approach, I then decided to structure the Congress around specific modules such as “Visual Pedagogies,” “Radical Readings,” “Situated Knowledges” and “Archipelagic Networks” and invite professors, curators, and artists with a particular interest in photographic, pedagogical, and feminist practices.

For instance, one of the first confirmed speakers was Carmen Winant, who also recommended inviting Sofia Cordova. Both are artists who identify as photographers who do not take photographs, and they will engage with the concept of friendship as a generative force in creative and teaching practice.

Andrea Jösch will discuss a pedagogy of images that challenges the “universal” history, and formal laws taught in technical schools, aiming instead to address the invisible and unseen. Susan Meiselas, Wendy Ewald, and Laura Wexler will present their recent book Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography, a pedagogical tool that reexamines photography narratives through the lens of collaboration.

Mariko Takeuchi, who received a Fulbright Grant for her research on photography education in the U.S., will offer a lecture on Japanese women photographers from the 1950s to the present, challenging the established canon of Japanese photography.

Another scholar, Emilie Boone, will highlight Haiti’s potential role in articulating the complexities of photography. Siobhan Angus will moderate a conversation with artists Rosell Meseguer, Kosisochukwu Nnebe, and Hiền Hoàng focused on materiality and the inextricable links between image-making and resource extraction as a precondition of photography.

The WOPHA Congress brings together over 35 national and international artists, professors, and curators, fostering a dialogue that not only addresses gaps in schools’ curricula, but also imagines new possibilities for the future of photography education.

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the underrepresentation and undervaluation of women and non-binary photographers in the broader landscape of photography and contemporary art. Despite their significant contributions, particularly from Latin American, Caribbean, and Latinx communities, their perspectives have often been marginalized. How does this Congress contribute to broadening this conversation, and what unique perspectives and narratives do these photographers bring to the forefront?

I am deeply passionate about this edition of the Congress, co-organized with Francisco Maso and Amanda Bradley, WOPHA Associate Curator of Programming. It centers on artists from Latin America, the Caribbean, and their diasporas, with a particular emphasis on South Florida, through panel conversations, exhibitions, and key institutional partnerships. This focus is central to WOPHA’s mission, as I see Miami as a border space—a political place—connecting the Americas.

The panel titled Caribbean Photography History explores the relevance of the Caribbean as a geographic region and as a theoretical framework for understanding the history of photography. This panel, featuring esteemed speakers such as José A. Navarrete, Emilie Boone, Roshini Kempadoo, and Tatiana Flores, delves into the Caribbean’s complex relationship with photography and the challenges involved in studying the medium’s history within this context.

Additionally, the Congress highlights other notable participants with deep roots in the region, such as Muriel Hasbun from El Salvador, now based in Washington D.C.; Keisha Scarville, who has Guyanese heritage; and Noelle Theard, born in El Paso to a Haitian father and French mother. Their work broadens the conversation around underrepresented voices in photography, particularly from an archipelagic perspective.

Amanda Bradley has also curated an exhibition titled In Between Sentiments at Miami International Airport, featuring emerging artists Nicole Combeau, born and raised to Colombian migrants in Miami, and Sue Montoya, born in Los Angeles and raised between Tegucigalpa and Miami. Through their work, these artists explore themes of identity, memory, place, and migration.

I believe the Congress leads by example. In a context where Latin American and Caribbean authors are often excluded from the history of photography, we are positioning their work at the center of the conversation through other partnerships with organizations such as Maison de la Photographie de Guyane-Amazonie and Foto Féminas.

In collaboration with the Caribbean Cultural Institute (CCI) at Pérez Art Museum Miami, we are also proud to present the second edition of the CCI + WOPHA Fellowship. Our 2024 fellow, Claudia Claremi, will spend a month in residence at El Espacio 23 this September, developing her ongoing series La memoria de las frutas. This large-scale, research-based project delves into the sensory and emotional connections people have with fruits, illuminating on the larger impact of industrial agriculture in the Caribbean, the migratory pathways of both fruit and people, the diminishing presence of fruit trees in Caribbean communities, and the challenges these communities face in accessing once-plentiful fruit.

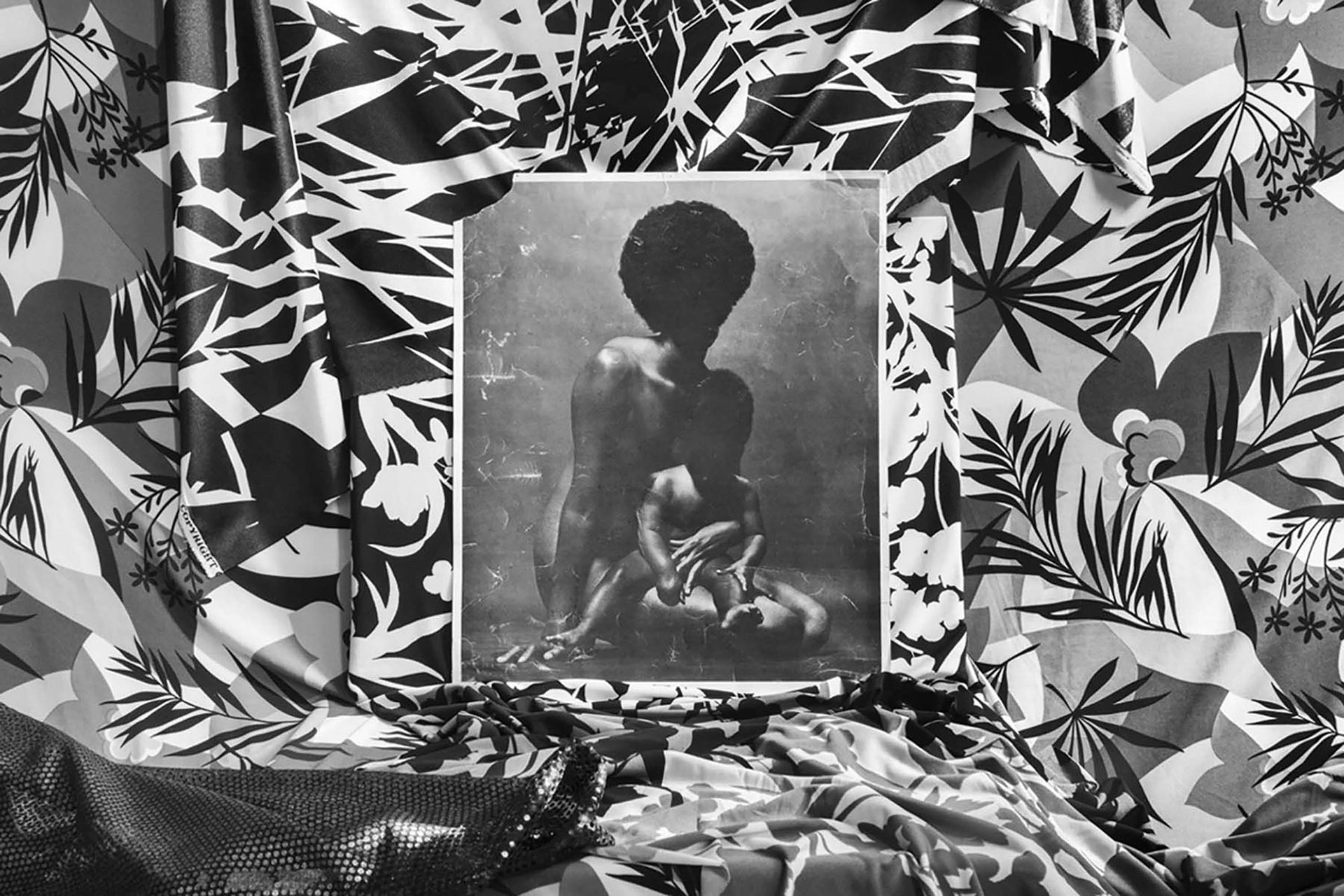

Keisha Scarville. Within/Between/Corpus (1), 2020. Photography. © Keisha Scarville. Courtesy of the artist.

Keisha Scarville. Within/Between/Corpus (1), 2020. Photography. © Keisha Scarville. Courtesy of the artist.

Assistant Laura Hubber

with translator As’ad Gozeh developing

and processing Polaroid film, Sulaymaniyah,

Northern Iraq, 1993.

Assistant Laura Hubber

with translator As’ad Gozeh developing

and processing Polaroid film, Sulaymaniyah,

Northern Iraq, 1993.

Veronica Sanchis Bencomo. Foto Féminas' Mobile Library. Photo by Ana Leticia Espinal. Courtesy of the artist.

Veronica Sanchis Bencomo. Foto Féminas' Mobile Library. Photo by Ana Leticia Espinal. Courtesy of the artist.