STRANGE FIRE COLLECTIVE | Q&A: Roxana Marcoci

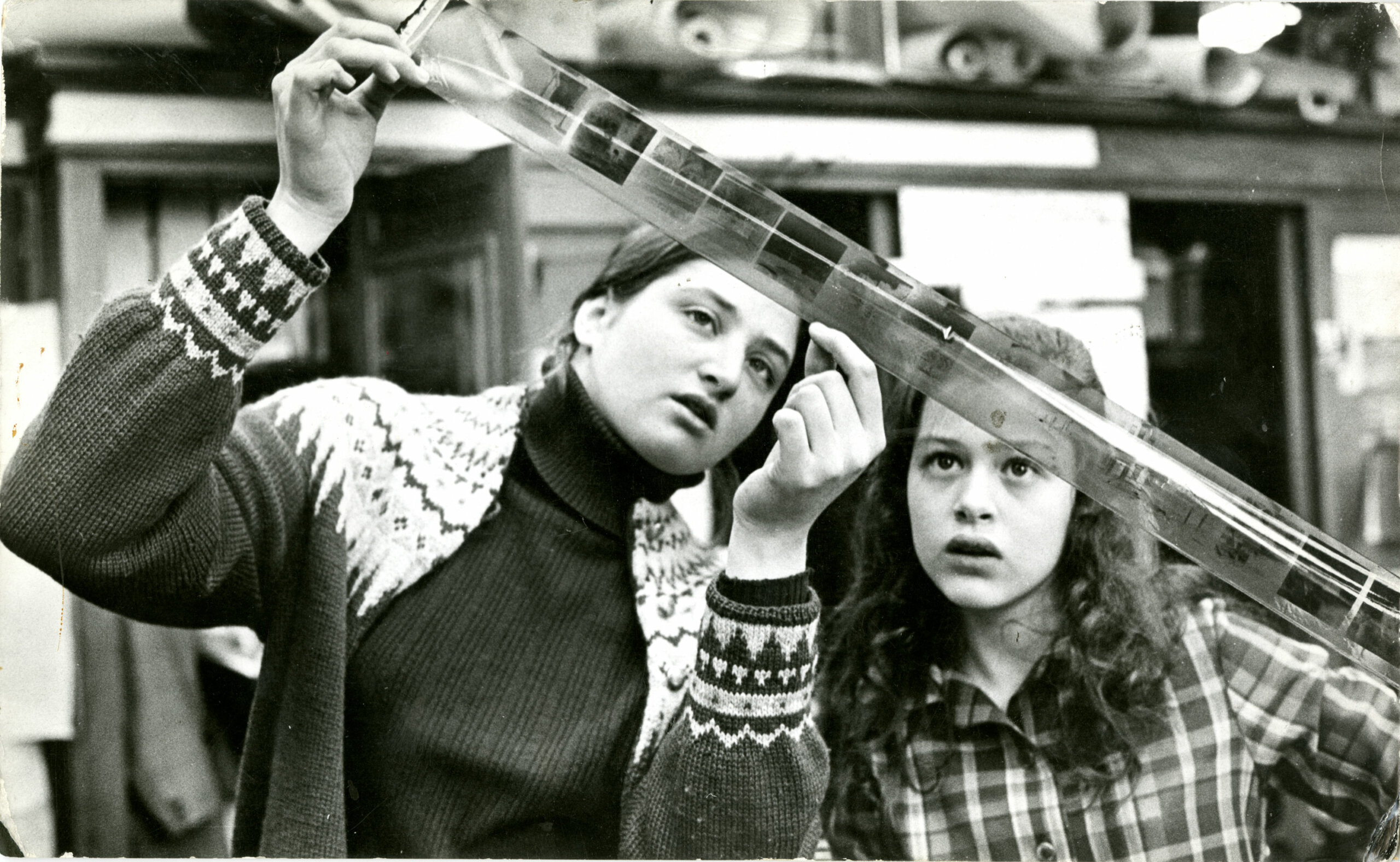

Roxana Marcoci presenting Zofia Kukic’s work in the exhibition “Transfigurations”, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Fall 2019

Roxana Marcoci presenting Zofia Kukic’s work in the exhibition “Transfigurations”, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Fall 2019

Rafael Soldi: Hi Roxana, thank you for taking the time to chat with us.

Roxana Marcoci: It’s a pleasure, thank you for the invitation.

RS: The world has experienced extraordinary circumstances in the last two years—how have these experiences influenced your curatorial approach for the years to come?

RM: I have long been aware of the need for museums and universities to reassess the monolithic narratives of Western art history, which have fueled the colonialist imagination. To reassess the ways we research, write, teach, collect, and exhibit. The last couple of years have only reinforced the urgency for inclusive curatorship and pedagogy, for promoting a sense of equity in the ways we define the ethics of attention. It’s critical for museums to foster a more diverse and inclusive community, to invite people in, center them, care for previously obscured histories, and reposition modernist art from our positions in the present.

I am not sure if you are familiar with MoMA’s C-MAP (Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives)—a pan-institutional research program founded in 2009. The initiative promotes the multiyear study of art histories outside North America and Western Europe and is currently organized into four research groups that respectively focus on modern and contemporary art produced in Africa, Asia, Central and Eastern Europe, and Latin America and the Caribbean. C-MAP has produced a Primary Documents Publication Series, books which contain meticulously edited translations of source materials relating to the visual arts of specific countries, historical contexts, disciplines, and ideas, together with newly commissioned essays and other archival materials. In tandem with these anthologies, C-MAP’s monthly seminars concentrate on transnational histories and nonaligned networks, multiple modernities, and involve international dialogues with a variety of cultural workers. A website, post, makes C-MAP’s research available to a broader public. For me the most prescient question is how can we respond to the call to decolonize art history? It’s a question related to how we can decenter an academic, and respectively museological, discipline grounded in racialized concepts. How do we create epistemic communities grounded in equitable partnership, forms of reparation, and other legacies—postcolonial, intersectional feminism, queer, indigenous?

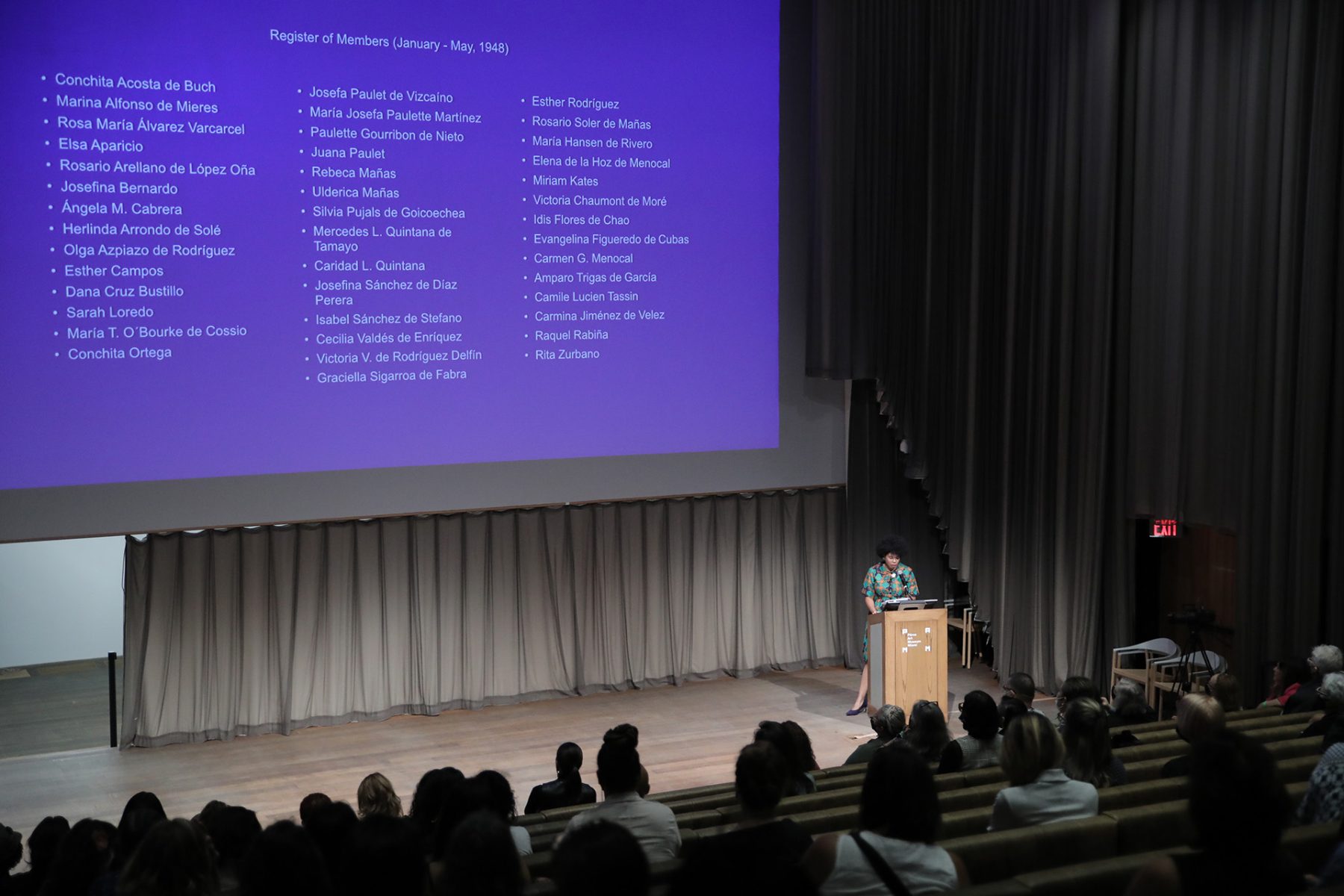

RS: You’re due to present at the upcoming WOPHA Congress: Women, Photography, and Feminisms this November. From Louise Lawler, to Carrie Mae Weems, Zoe Leonard, Taryn Simon, and Sanja Iveković, you’ve worked with many profoundly impactful women throughout your career. Can you speak to the work you’re doing to highlight women and feminist perspectives within an institution that is historically male-leaning in terms of its holdings and exhibition history?

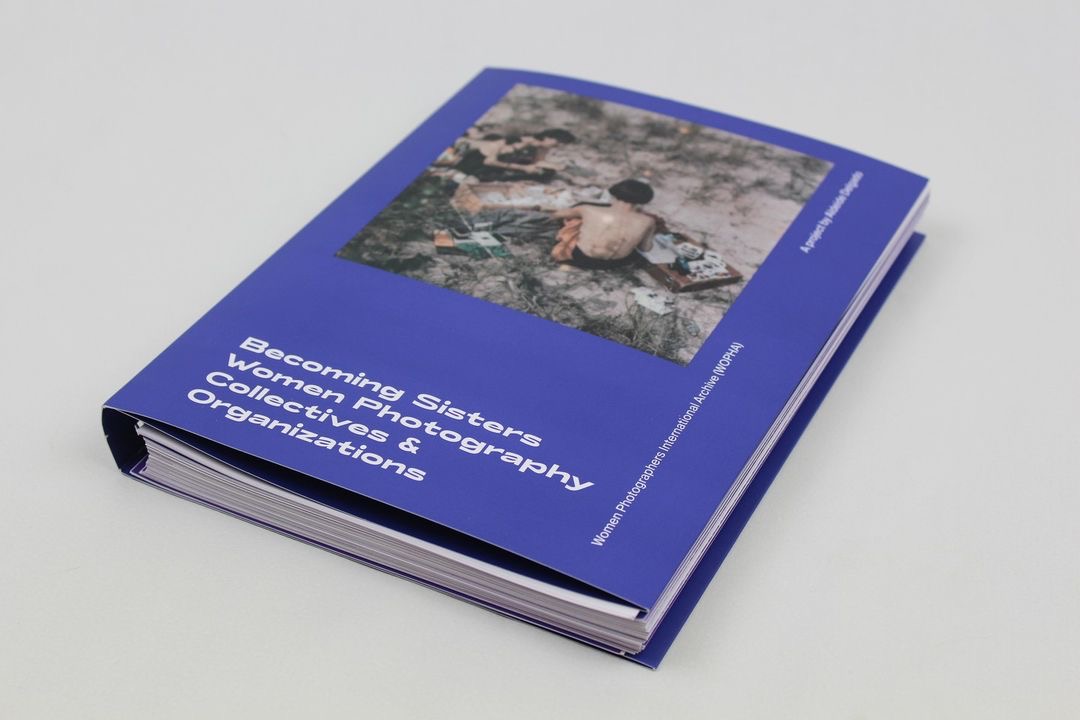

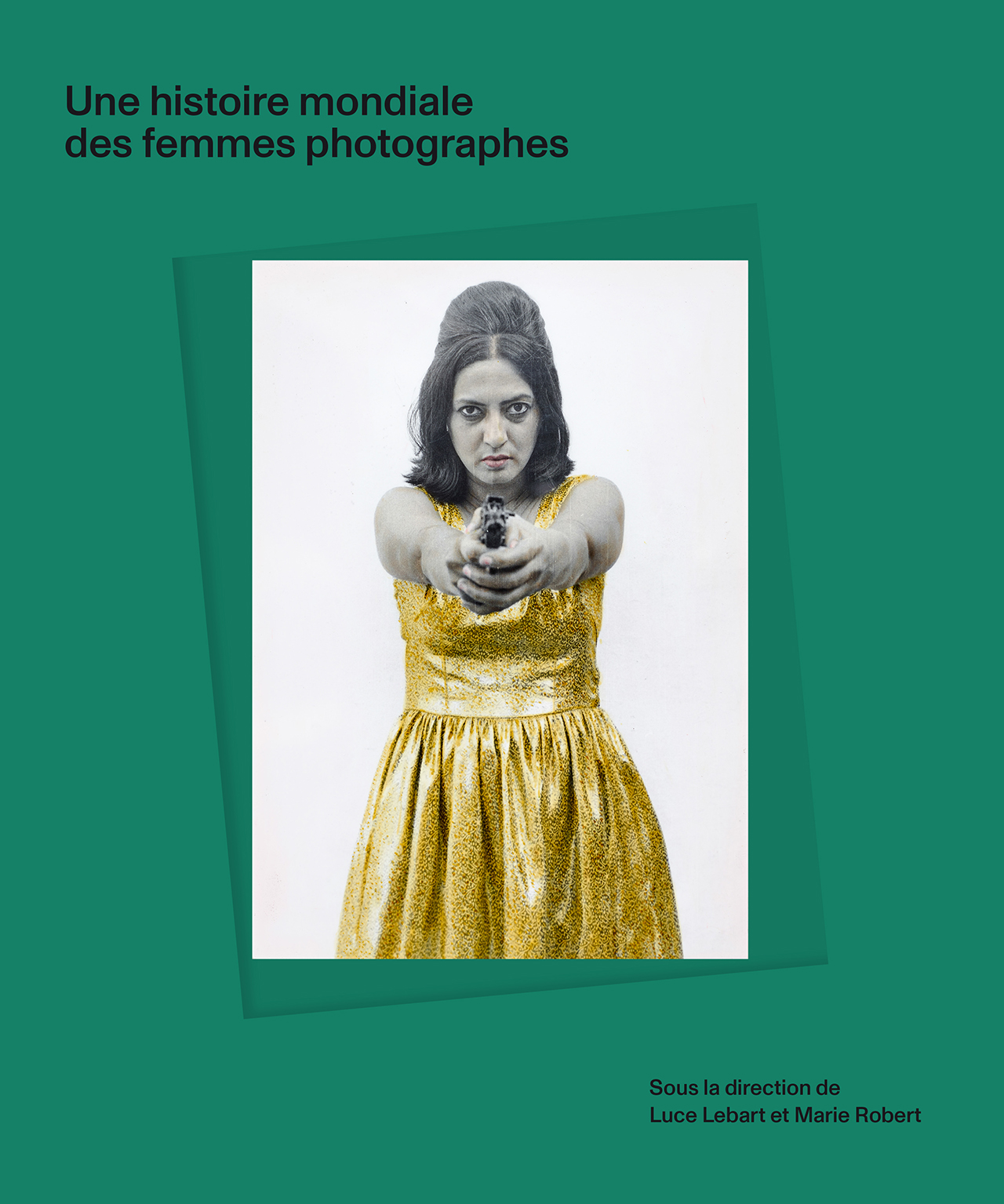

RM: I have and will continue to foreground the work of women artists in all aspects of exhibition-making, collection, seminars, and publications. Right now, I am working on an exhibition titled Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists, which will open at MoMA in April 2022. It is accompanied by a book that covers 100 years of photography, part of a transformative gift to MoMA of works by women artists from psychotherapist and women activist Helen Kornblum. The project will bring forward a diversity of practices—including portraiture, photojournalism, social documentary, advertising, avant-garde experimentation, conceptual photography, and performative actions. The exhibition’s premise is that the histories of feminism and photography have been entwined. African-diasporic, queer, and postcolonial/Indigenous artists have brought a change of perspective to the specifics of gender politics. The book includes a critical essay that I wrote addressing the question: “What is a Feminist Picture?”; and a series of shorter thematic essays by emerging scholars Dana Ostrander, Caitlin Ryan, and Phil Taylor that explore themes such as identity and gender, the relationship between educational systems and power, and the ways in which women artists have reframed our received ideas about womanhood. Rather than presenting a chronological history of women photographers or a linear account of feminist photography, the project forges compelling dialogues among the works to activate new readings from the angle of a contemporary, intersectional feminist perspective. I like this approach because it offers both historical context and critical interpretation of the myriad ways diverse photographic practices might be construed through a feminist prism. By looking at the intersections of photography with feminism, civil rights, Indigenous sovereignty, and queer liberation, Our Selves will contribute vital insights into figures too often excluded from our current cultural narratives.

At the same time, I also work with male artists who embrace a feminist outlook. This is the case with the exhibition Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, which is scheduled to open at MoMA in September 2022. An incisive observer and a creator of dazzling pictures, Tillmans has experimented for over three decades with what it means to engage the world through photography. He considers the role of the artist to be, among other things, that of “an amplifier” for social and political causes, and his approach to artmaking is closely connected to a concern with the possibilities of forging connections and the idea of togetherness. The exhibition and the two Tillmans publications that I am preparing (involving a Reader of his interviews, short essays, lyrics, and Instagram posts, and a comprehensive exhibition catalogue), foreground the ways in which this artist’s concern with the social, with activist causes (including feminism), and his ethics of care are inextricable from his ongoing investigation of what it means to make pictures. I like this quote, in which Tillmans says: “I see my installations as a reflection of the way I see, the way I perceive or want to perceive my environment.” And then, “They’re also a world I want to live in.”

RS: A collection as vast as MoMA’s undoubtedly has gaps too. Within your department, what are some areas you are excited to strengthen and deepen in the collection? As a curator do you see this as an opportunity to leave a mark on the institution and build a legacy around topics you deem critical?

RM: MoMA’s acquisition strategy is grounded in the idea of the living museum model, the museum as an open system of potential relations rather than a storehouse of frozen facts, as a network of possibilities rather than a static formation. Careful observers of MoMA’s collection installations will notice an emphasis on women-centered and social-justice contents. I like to always take cues from the ways artists show us how to do the work of reimagining and remaking our existence in the world. Intersecting feminisms, hybridization of traditional and new media, performance, the digital/Internet, and Black, trans, and queer visual culture are at the forefront of my research. I’m also interested in transnational approaches that challenge and revise dominant art histories. I’ve been thinking in the past few years of the archipelago model, a postcolonial model of composite cultures developed by Martinican cultural theorist and poet Edouard Glissant (the reverse of the global and uniformization) as a path marker.

RS: You co-founded the Forums on Contemporary Photography at MoMA over a decade ago. Is there any one presentation over the years that was particularly memorable or that made you reconsider a topic in a new, unexpected way?

RM: There are quite a few. If we were to put all the forums together, it would amount to a critical anthology of the first two decades of the 21st century. Perhaps I should mention in this context just the last three forums, all from 2021, since each was a tribute to a feminist artist or feminist theorist of visual culture. In February, we presented A Tribute to Carrie Mae Weems, which I co-organized with Sarah E. Lewis, Associate Professor at Harvard University. The event was a double celebration—of MoMA’s exhibition of Carrie Mae Weems’s poignant work From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, which I had the honor to curate; and of the Carrie Mae Weems anthology, part of the October Files series, edited by Sarah with Christine Garnier, 2020–2022 Wyeth Predoctoral Fellow, CASVA, National Gallery of Art. In April, we convened the 50th Anniversary of Linda Nochlin’s “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Recognized as a keystone of feminist art theory, this incisive essay along with its 2001 follow-up reappraisal, “Thirty Years Later,” a text highlighting the development of intersectional feminisms during the 1990s, changed the makeup of art history by exposing the institutional barriers to the visual arts that women have historically faced. As a scholar and pedagogue, Nochlin perceptively expressed how art criticism and social activism could inform the struggles against systemic inequality and exclusion. I co-organized that forum with writer Julia Trotta (who is also Nochlin’s granddaughter). The event celebrated the occasion but also historicized and illuminated more recent shifts in the world (MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements) and the discipline of feminist critical theory that has made possible the understanding of Nochlin’s prescient interventions. In October I co-organized with my colleague Thomas J. Lax, Curator in Media and Performance at MoMA, Black Gazes, a forum dedicated to Tina M. Campt’s new book A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See (2021) and of contemporary artists’ attempts to shift how we interact with visual culture by reclaiming discomfort, refusal, and the work of feeling alongside one another.

RS: It’s a wonderful book, I just finished reading it and it’s so powerful. What current or upcoming projects are you excited about?

RM: I am very excited by MoMA’s “Fall Reveal”—a new series of installations across three floors of collection displays. Within that context, I have collaborated again with Thomas Lax on the exhibition Critical Fabulations. The title comes from an essay, “Venus in Two Acts,” authored by Saidiya Hartman, a renowned scholar of African American literature and cultural history whose work explores the afterlife of slavery in modern American society. The text brings up the method of “critical fabulations,” which “troubles the line between history and imagination.” Hartman’s innovative writing illuminates Black stories that have long gone untold, that historical archives have omitted or obscured. This is the point of departure for this exhibition, which brings together artists Deana Lawson, Dalton Paula, Cameron Rowland, Tourmaline, and Kandis Williams whose creative use of archival materials, oral histories and historical artifacts reimagine Black futurity. Hartman’s essay was first published in 2008 in Small Axe, a Caribbean journal of criticism, in an issue on the archaeologies of black memory. We republished it in collaboration with Cassandra Press, a Black publishing imprint and pedagogical platform founded in 2016 by Kandis Williams. It’s all about the labor invested in the narration and acts of reparative Black futures that this exhibition buttresses.

RS: Thank you, Roxana. I look forward to hearing you speak at the upcoming WOPHA Congress and to experience the upcoming exhibitions and publications you’re developing.