CONTEMPORARY AND | In Conversation Aldeide Delgado and the Women Photographers International Archive

Adama Delphine Fawundu. Earth seed New York State, 2017. © Adama Delphine Fawundu. Courtesy of Adama Delphine Fawundu

Adama Delphine Fawundu. Earth seed New York State, 2017. © Adama Delphine Fawundu. Courtesy of Adama Delphine Fawundu

We spoke to the founder of WOPHA about rediscovering forgotten female Cuban artists and photography’s many uses – including its ability to provoke change.

Contemporary And: What is WOPHA and why did you establish it?

Aldeide Delgado: WOPHA, Women Photographers International Archive, is a nonprofit organization founded to research, promote, support, and educate, in partnership with other international organizations, about the role of those who identify as women and non-binary in photography. It evolved following a five-year examination of the contributions of women to the history of Cuban photography from the nineteenth century to the present for the Catalog of Cuban Women Photographers (Catálogo de Fotógrafas Cubanas).

When I moved to Miami in 2016, I was already focused on expanding my scope of work and I thought it was important to adapt to this country and city in the context of my work as an art historian. I was surprised that in this global city, whereArt Basel Miami Beach has become a cornerstone and there are so many international initiatives and aspirations from the artistic community, there was nothing related to photography. My ambition was twofold: to establish a project with international scope while maintaining a strong focus on the academic component – there could be dialogue about the cultural appreciation for photography and research at university level.

C&: WOPHA has a strong focus on historical research, and the notion of erasure is an important leitmotif. What does your research involve?

AD: I am an art historian by practice and I have an abiding love for the past. When I began the process of establishing the archive I was confronted by the lack of material on Cuban women photographers working before 1959. Lacking actual photographs, I conducted interviews and combed through magazines and newspapers trying to find work that oftentimes was not saved by the families of even very notable artists, like Chea Quintana. This was shocking to me, and I was driven to create a space to preserve work that was underrecognized during these women’s lifetimes. It was particularly rewarding when my work led to the correct identification of work by Abigaíl García Fayat that had been donated to the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago and previously described as anonymous. I operate under the premise that you can’t speak about what is happening today without recognizing the work of our predecessors, and my mission is to make that information accessible and available online.

C&: Women, queers, and people of color have problematized the medium of photography. How do you deal with concepts like “woman,” “photography,” and “feminism,” which are constantly discussed and in motion?

AD: These changing concepts are one of the main reasons I created the WOPHA Congress – to initiate discussions with the preeminent women photographers, art historians, and curators of our time. When I started the catalogue project in 2013, the discussion was around women and we didn’t have this movement around feminism. Now we are seeing that the cultural focus has expanded to include non-binary, trans, and queer people, and we need to ask whether these organizing titles have become reductive. For me, the question is whether “women” is still a useful category or whether we should speak about everything else. What are the works teaching us? Who is behind the camera ideologically, irrespective of gender, sex, skin color, sexual orientation, or how they identify?

With regards to feminism, we know the work is not done. There are even difficulties with the word feminism, which is why we employ it in plural form in the title of the inaugural Congress: “Women, Photography, and Feminisms.” We also need to acknowledge that there is a long tradition of feminists in this country, who have not recognized the experience of marginalized women in other countries. So we need to speak about feminists, but we also need to speak about the fights of women everywhere to get more recognition and representation. I ascribe to the premises of bell hooks as well as to Paul B. Preciado, who posits that the subject of feminism doesn’t need to be women, but rather the transformation of all society.

This is why I’ve always been very clear that with WOPHA everyone is welcome. We are doing work with women, but this conversation cannot happen if men are not part of it too.

C&: In an interview, you quoted the art critic Abigail Solomon-Godeau: “The history of photography is not the history of remarkable men, much less a succession of remarkable pictures, but the history of photographic uses.” What photographic uses do you find within the photographers participating in WOPHA?

AD: As a researcher with an empty canvas trying to decide where to begin, my approach was to examine how photography was consumed during specific periods. For instance, in the nineteenth-century studio photography was about how the public interacted with the photography world, then postcards became prevalent, then in the early twentieth century perceptions of photography among the masses completely changed through documentary photography and journalism. It is through the examination of these uses that you can find women photographers who have been forgotten and erased.

Another aspect to usage that warrants examination is how photography has the ability to provoke change by illustrating conflict. Take for example the work of Maria Kapajeva, who will speak at the Congress. Her series depicting the peripheral histories of mill workers in her hometown was used in the Estonian Parliament to illustrate the plight of workers denied sick leave.

C&: I’m fascinated by the current online abundance of selfies, of portraits. Especially for marginalized people, it seems to be the most accessible way to inscribe oneself in the world’s largest (alternative) image archive – until one can no longer be erased. And yet platforms like Instagram intervene, and the censorship of bodies read as female is inescapable. But there are also many attempts to subvert these restrictions photographically. Is photography today more an act than document of a single observation?

AD: Photography has never been about the object. The theorization that will occur at the Congress when we speak about photography as a collaborative practice will endeavor to highlight the social interactions that happen behind the photographic art. We need to shift the focus of attention to the process and the interaction between the subject, the person documenting the image, and the observer.

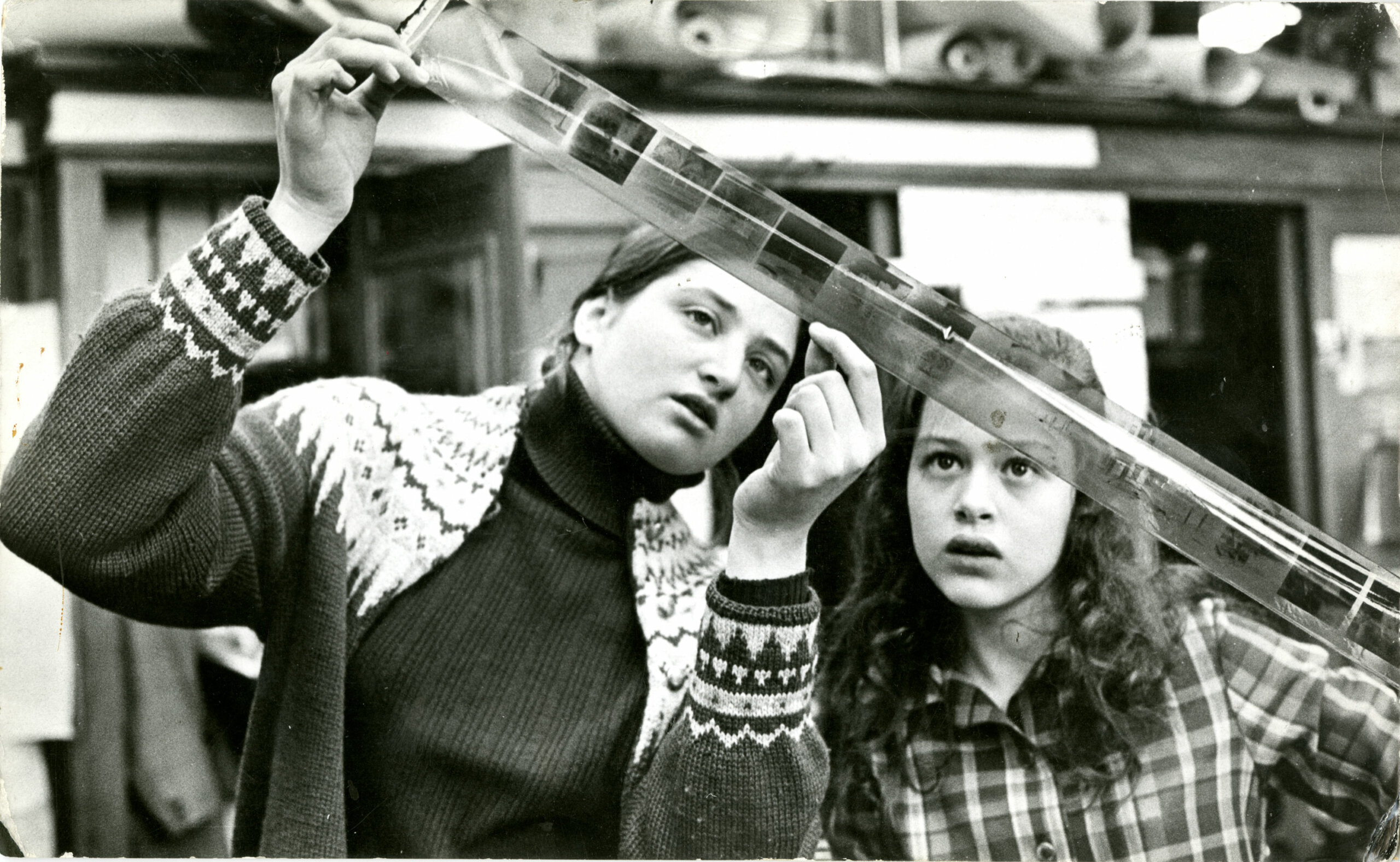

One of the works that is important to me for this reason is El Picnic by Nereida García Ferraz in collaboration with Laura González Flores and Eugenia Vargas Pereira. It is a project about photography, but it speaks about its relational component and the interactions that occur therein.

C&: The first WOPHA Congress will take place at the Pérez Art Museum Miami on 18–19 November 2021. What can we look forward to?

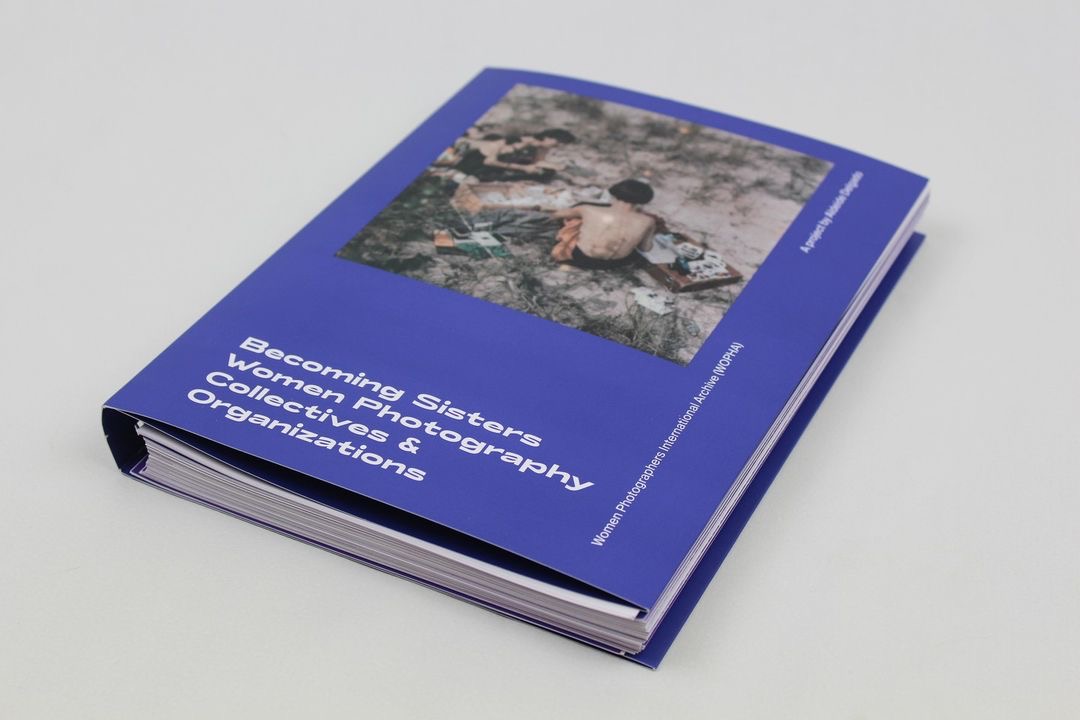

AD: From a personal perspective, the gathering of representatives of forty international women’s and non-binary collectives and like-minded organizations from around the world on the eve of the Congress is the most urgent aspect, because it speaks directly to the very impetus for such an event. The creation of collectives or communities of women photographers based on solidarity and networking has been a fundamental strategy used historically and in the present to highlight the contributions of women in the photographic arts. During this landmark private meeting of the minds, we will have the opportunity to speak frankly and set guidelines for the work we are doing. The publication of the new WOPHA photobook Becoming Sisters: Women Photography Collectives & Organizations will commemorate the occasion and serve as a registry and collective manifesto reframing the dominant narratives of photography history.

As part of the public program for the Congress, I’m also extremely excited to bring to Miami an exhibition featuring works by the winners of the prestigious Female in Focus award in collaboration with 1854 Media and its British Journal of Photography at the new Green Space Miami. Further, toward the goal of establishing Miami as a hub for photography, I am also looking forward to presenting WOPHA’s first artists in residence, Adama Delphine Fawundu and Nadia Huggins, for 2021 and 2022 respectively. Through partnerships with El Espacio 23 and The Betsy, they will be connected to the South Florida academic and creative communities via studio visits, artist presentations, classroom conversations, and exhibitions.

The closing conversation presented by Ibeyi artists Lisa-Kaindé, Naomi Diaz, and Maya Dagnino will also be a highlight of the Congress. Titled In Our Glory: Spirituality and Representation in Photography, the presentation will reveal a new dimension to Lisa as a visual artist beyond her work as musician, while also expanding the dialogue around these pressing issues to a wider audience in both a physical and intellectual sense.

This interview was originally published at Contemporary And by Miriam M’Barek.

About

Miriam M’Barek works between art, politics, and its criticism. She focuses on contemporary culture at the intersection of race, gender, and sexuality – and involves in institutional criticism and artistic research on post-migrant identity politics.

Contemporary And (C&)is a dynamic space for the reflection on and linking together of ideas, discourse, and information on contemporary art practice from diverse African perspectives.