STRANGE FIRE COLLECTIVE | Q&A: Luce Lebart

Newsha Tavakolian. Portrait de Negin à Téhéran, 2010. © Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum Photos. Courtesy of Editions Textuel.

Newsha Tavakolian. Portrait de Negin à Téhéran, 2010. © Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum Photos. Courtesy of Editions Textuel.

Luce Lebart is a historian of photography, curator, and French correspondent for the Archive of Modern Conflict collection. She directed the Canadian Institute of Photography from 2016 to 2018 and the collections of the Société Française de Photographie from 2011 to 2016. Her research focuses on archival photography, the history of techniques, scientific and documentary practices relative to image. She was the curator of (among others): Souvenirs du sphinx and Lady Liberty at the Rencontres d’Arles; Illuminations (Foto/Industria, Bologna); Frontera (National Gallery of Canada) and Gold and Silver (MBAC and FOAM Amsterdam, 2018). She has published several books, including Les Grands Photographes du XXe siècle (Larousse, 2017).

Rafael Soldi (RS): Hi Luce, nice to be chatting with you, from opposite sides of the world. So, tell me about your path to where you are today with photography and as a curator. How did you get here?

Luce Lebart (LL): My love for photography started when I was a child. I immigrated with my family from North Africa, and we had a suitcase filled with photos. During the holidays I used to spend lots of time going through these photos and trying to better understand the past. I studied at the National School of Photography in Arles, and I started working in museums, libraries, and collections because I was very attracted to archives, much like the one in our suitcase growing up. I developed a research practice but came late to curating; I was invited to curate an exhibition in Arles about10 years ago and I really enjoyed it. And since then I’ve curated many shows around the world. My main subject is really photographs that have been produced without an artistic intention, but photographs that still have a huge aesthetic potential.

RS: And what can we expect from your upcoming presentation at the WOPHA Congress: Women, Photography, and Feminisms?

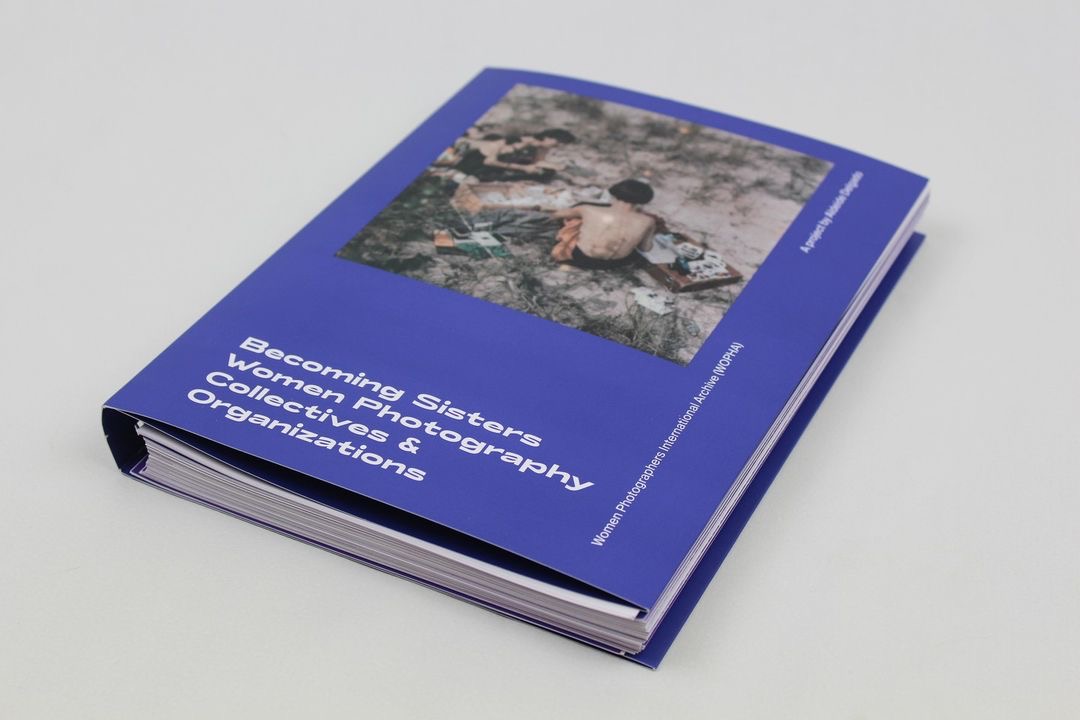

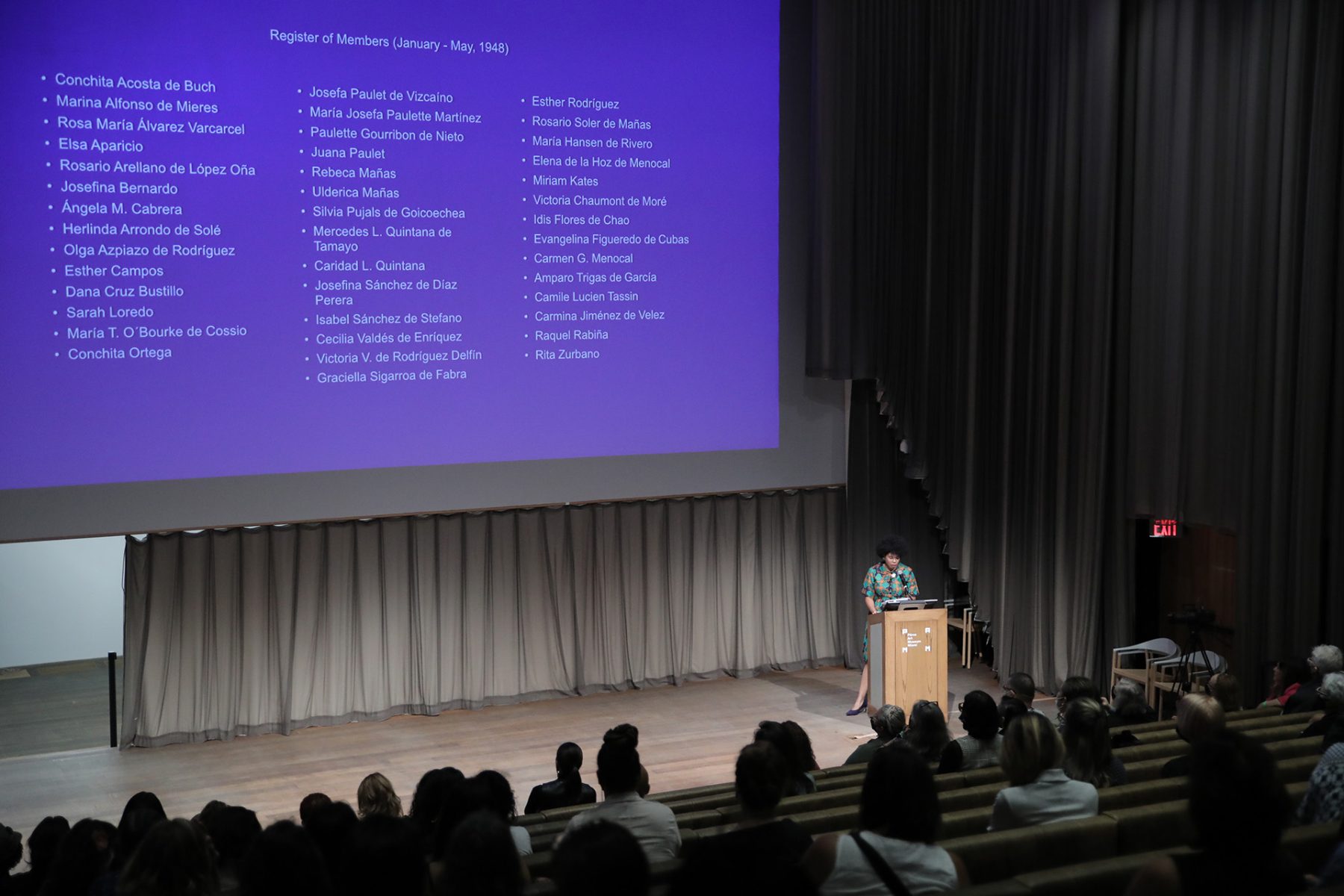

LL: At WOPHA I will present the book that we’ve made, Une Histoire Mandible des Femmes Photographes. It’s a worldwide history of women photographers, which has been published in French but is now going to be published in English. I’m going to tell the story behind the book, how we made it, because it’s a huge adventure! It includes 300 photographers from the 19th century to now and features 160 women authors. And the idea was to give voice to women authors and photographers who have been overlooked throughout the history of photography. Another goal for us was to decenter the narrative by highlighting authors and photographers from all over the world—most of the books that are easily accessible center the narrative on American and European artists. So we really wanted to find an example of practices in places like Haiti, New Zealand, Africa. At first, we followed our intuition; for example, we recently realized that here in Europe there were women photographers in the 19th century. So we have this hypothesis that there were likely women photographers in the 19th century in other parts of the world as well, like in Panama. We collaborated with many researchers around the world, and the more we researched the more incredible women we found around the world. For example, in Panama, we were worried we may not find any women and in the end, we found more than fifty! Because we ended up connecting with so many passionate and excited people who were committed to bringing forth diverse narratives and rescuing forgotten histories. And then it was terrible because we had too many! So I’m hoping to expand on this whole process at the WOPHA presentation.

RS: So it sounds like that research process must have been so rewarding and so exciting.

LL: Yes. Well, it was also very challenging because to do such a work at this scale we really needed funding. We’re fortunate to have found in our publisher a very committed woman. She never stopped believing and asking for funding to bring this project to life. We also did the book in one year, which was very intense. We had already done a lot of work to build the network but once the funding came through, the clock started and we only had one year to pull off this big project that had so many contributors and moving parts! But as soon as we got the ball rolling, all our contributors hit the ground and things moved very quickly. I think it’s a moment in history where many people are realizing that women have been overlooked, not only in the history of photography but in all the fields of knowledge, science, politics. So people were very excited and it grew very organically.

RS: I can imagine! And along the way, I’m sure there were a lot of surprises and wonderful discoveries. Are there any memorable experiences or discoveries that stayed with you?

LL: I couldn’t say anyone photographer but one thing that was memorable about the process was that because our contributors were all over the world, the process also mirrored what was happening in those places. For example, our correspondent in Beirut, Lebanon, was affected by the protests, and her institution was closed. With others, we were dealing with opposite time zones. But one experience I do remember was toward the end of the process, we were trying to connect with an important photographer whom we felt needed to be part of the book. She was unable to participate in the end but pointed us to another artist who wasn’t on our radar. So I reached out to this new contact, but she asked if we had included Donna Ferrato in the book. So I said, oh, no, no, no, but it’s finished, we already have 300 women, we can’t add anyone else. So she said well, it’s too bad, but let me tell you a bit about her. And I loved hearing her voice on the phone telling me about this artist I didn’t know. Ferrato had been on an assignment for Japanese Playboy where she witnessed and photographed an altercation that led her to a long-term project documenting domestic violence that helped change the law in the United States. So she was part of this amazing change, and I told my colleagues, we cannot stop at 300, we have to add her. And we already had too many American photographers but we just felt this work was too important. And I love how this happened because it is what happens when you have these encounters and conversations—to me I was just so enthralled by her voice sharing this story over the phone. One woman making a case for another woman. It was so special.

RS: So I want to switch gears a little bit and talk about your love of vernacular photography. You’ve worked a lot with archives in many different ways, including a personal project of yours and some work with The Archive of Modern Conflict (AMC). I saw Collected Shadows back in 2013 in Vancouver at The Polygon Gallery, when it was still called Presentation House. I was blown away by this show and the archive, can you talk more about your involvement with the collection?

LL: When Timothy Prus curated the show you saw in Vancouver I wasn’t working with them yet, but I got to see the show at Paris Photo, because this show has traveled a lot. When I saw the show I was in shock because it felt very different and new to me. There were very well-known photographs by people like Daguerre exhibited alongside vernacular images, scientific images, et cetera. This is not an entirely new idea in America, where Julian Levy was exhibiting Duchamp alongside Atget in the 1930s. But regarding the way we exhibit heritage photography here in Europe, the Archive of Modern Conflict really shook things up.

Also here in France, in particular, the discourse around photography was increasingly academic and at some point, it’s almost as if writing was more important than seeing and sharing images. And I feel the Archive really reversed this and I found it very exciting. So now I collaborate with the collection and we’re preparing a new show that will open in Vancouver at The Polygon in 2022. It’ll be about clouds and vernacular photography.

RS: And the new space at The Polygon is so different from the last one. It’s more airy and open to the sky. The other space was more cavernous.

LL: Yes it is! And you know, even though I’m a historian of photography, it’s very important for me to keep a creative approach to the history of photography.

RS: How many items are in the AMC?

LL: Over 4 million!

RSi: Now tell me a little bit about your book, Mold is Beautiful, which has an archival context.

LL: Before being a curator of exhibitions I worked as a curator in institutional collections. I also directed the collection at the French Society of Photography, which is the first association of photography created in 1851 and is a very prestigious institution. While I was there we were doing inventory once and I discovered a wooden box under a shelf and inside there were autochromes and gelatin silver prints with traces of a past flood. Honestly, the box was being used to balance out the shelf! When I looked at them, I saw that some of them were totally amazing. I decided to do a book to give them new life, and you know, when you work in an archive mold is your enemy. I wanted to show the aesthetic power of this microorganism, the aesthetic power of an image that is created without an artistic goal, but that is so beautiful and abstracted.

What Was very interesting was that often the damage would meet the content of the image. For example, in some glass plates, there’s a sort of Milky Way formed from the gelatin that has detached from the plate and it worked beautifully in context. I worked with a publisher who I had worked with before and we decided to make a book rather quickly. It was a kind of manifesto as someone who was in charge of a collection that should not have moldy photos in it!

RS: Do you see these as artworks of your own or do you see them simply as beautiful objects that you wanted the world to see?

LL: It’s a complicated question but I love this question. I’ve learned with photography not to be so sure about the borders between art and the document or an archive, and this is what I love in photography. The way these lines are blurred and this ever-changing status is such a characteristic of the photographic medium, this questioning of what is art.

RS: Are the images in the book as you found them, or did you intervene further beyond documenting them?

LL: I didn’t intervene so much, maybe some color correction or basic adjustments but they’re pretty much as they appear in the book. But for me, that’s not a criteria for what makes something art or not. For example, Sherrie Levine made exact copies of existing work by other artists.

RS: That’s true. I was asking that primarily because the colors are so beautiful and I didn’t know if they were added or the objects looked that way.

LL: The colors were already there. And you know, when I found them I showed them to our preservation specialist and he said he had never seen some of these microorganisms. The way they bubbled and the color was very unique. What was very important was the work of editing. What was very important was the work of editing, choosing the right works that would work in the book format. And I’m working on a new follow-up book about an archive that I collected for years. I’m very happy about that.

RS: This is a perfect segway to my last question. I just wanted to know what you were working on and if there was anything else you wanted to share with us before we, we wrap this up.

LL: The most exciting project right now is this follow-up to Mold is Beautiful.” I’m also working on a book of interviews with artists working with plants, photosynthesis, and photography. I’m also researching and writing about photography, cooking, and chemistry. I’m connecting contemporary artists with the imaginary of the beginnings of photography, the archeology of photography, the imaginary of technique. And I’m also working on a project about the history of the darkroom.

RS: All of those projects sound wonderful and incredibly diverse. I feel like you have a very diverse practice.

LL: Yes, but there is a link between it all. I’m often very interested in things that have been overlooked. Whether it’s moldy photos, or documentary practices, or women photographers, I’m always searching for topics that are unexplored. That’s the thread.

RS: That must make your work very rewarding, you’re part-curator part-investigator!

LL: Yeah, exactly!

RS: Thank you so much for your time, Luce. I really appreciate it.

LL: Thank you, it was really nice talking with you.